294

A mentor in the philosophy department once posed an interesting question: "Could you be the same person if you were the opposite sex, living in the 18th century?" I came to think: yes. That's because I see myself primarily as a perspective, and a perspective need not have a particular gender or time. A perspective does, however, often long to be expressed. My definition of a philosopher is, "someone with the compulsive need to express a point of view," and I am, in the end, a philosopher. I've been writing songs, stories, and philosophy for many years now, and finally got around to putting them in one place, for your consideration. These are my dancing shadows. This is my perspective.

Portland Is

1. rain

2. uber polite motorists stopping in the middle of a block to let you enter traffic (if in a car) or to cross the street (if on foot)

3. Hipster in ill-fitting gray suit from the 40's with lime green sneakers. Beard optional.

4. A large chunk of the population (30% 40%?) that doesn't give a fuck what they look like. Not anti-style so much as no style.

5. warmth. soul. approachability.

6. blooming, bursting fecundity - every sort of flower, tree, moss, plant, grass, bush, weed, growing magnificently everywhere.

7. big city downtown junky crime old building port city funk

8. smoking. drinking. comfort food. A pot dispensary on every corner

9. street people with signs begging at the entrance of most stores. Aggressive panhandler shouting from a block away "you got fifty cents?"

10. parents carrying children in their arms instead of expensive strollers

11. half the girls of a certain age (10-13?) putting color in their hair. Green, pink, purple, red, and combinations thereof

12. a class of schoolchildren walking two by two, hand in hand down the sidewalk. Okay, that happens everywhere. Isn't it nice?

13. Rain

Late Fragment

And did you get what you wanted from this life,

even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel

myself beloved on the earth.

-Raymond Carver

We were somewhere around Barstow, on the edge of the desert, when the drugs began to take....actually, we were traveling from the Outer Banks of North Carolina to the family Christmas party in D.C. My brother, his wife, and their son were in one car and I was in another. Bryan had insisted that we caravan to the party. I didn't wonder why until we stopped for gas and my nephew Sumner decided/was told to ride with me. I still didn't think much of it. Maybe Sum was tired of hanging with his parents.

We arrived at my sister's house. The family did what families do. Talk was talked, food was eaten and then it was time to play the present exchange game. Each person chose a number and picked a gift in order. If you had a higher number, you could take one of the previous gifts from a sibling, and that person would choose again. My sister Kelly made her way around the room with the hat that held the numbers. I got number sixteen, the last choice of all.

Again, I didn't make much of the mischievous grin on Kelly's face when she distributed the numbers, or the little looks people kept giving me. It was just another Christmas party. Something was going on, but something was always going on with our family.

It was finally time to choose the last gift. I looked around the room and didn't see any presents I particularly felt like stealing. Kelly brought a great big box to me.

I peeled the paper and opened the box. I saw layer after layer of bubble plastic and said, "Great. Someone gave me a great big box of bubble plastic." Everyone laughed and crowded around. There was an air of expectation.

I found an owner's manuel for a computer and said, "Great, someone gave me computer instructions." It's common knowledge that I'm a Luddite. I figured this was part of a practical joke. My brother Curtis said, "Keep going, dig a little deeper."

At the bottom of the box was an Apple laptop computer. I pulled it out and looked around at my family. They had given me a computer! Everyone chipped in after Kelly discovered I was still writing my philosophy lectures out by hand. As I looked around the room, I saw the same look on each face. My family loved me. You go through life hoping that you're loved, thinking it, assuming it, but in that moment I saw it.

They had set the whole thing up. The hat that Kelly passed around had only number sixteens in it, ensuring I would go last. Everyone else went up randomly to pick their gifts. They told Sumner to ride with me because everyone knew that there was always a chance I would take a wrong turn and get lost on the way to the party.

Later, I opened the computer and began the long, strange journey into cyberspace. Folks gathered around and shouted out things to write. I scrambled to find the letters with my bony finger. I hadn't even typed before. I had a long way to go, but it was a heck of a way to begin living a larger life.

295

The night I saw Stevie Wonder. It must have been Jan. 3, 1982, my eighteenth birthday. Two friends and I decided to check out some nightclubs in Georgetown, the trendy part of D.C. It was the last year that eighteen year olds could buy beer in Maryland or D.C. After that, you had to be twenty-one.

Lea was one of my best friends. We had a band with his brother Steve and had been through many an adventure. Brad was his friend from the jazz band at school. We drove to M street and parked. Not knowing a thing about which club was which, we wandered into a little saloon called The Saloon.

The Saloon was an unremarkable room with a long bar against the wall. There were eight to ten four top tables in the seating area and an excellent jazz trio was working their way through standards in the corner by the window. It seemed like a cool place to grab a brew.

We bought a pitcher or two and settled in. This was going to be the first stop in what was to be an epic night of partying. We were young and strong and it felt great to be legal for a change. We toasted and kicked back to see what the night would bring.

What the night brought was Mr. Stevie Wonder. We were just pouring the last of our first round when who should walk in the door but the man himself. He was shorter than I had imagined, and built like a football player. He had a taller security guy with him, and kept a hand on his arm. No canes for Stevie Wonder. They sat at a table in front of the band. Stevie started swaying from side to side just like when he's performing. There were about twelve people in the bar.

Within fifteen minutes the window facing the street was crammed with faces of people trying to catch a glimpse of the man. Brad, Lea, and I toasted our fantastic luck. After a couple songs, Stevie's man helped him over to the piano. Stevie Wonder started playing for the twenty odd people in the bar as the bass player looked over his shoulder to catch the chords.

He started with "You Are The Sunshine Of My Life." After he sang the first line he said, "I love to sing." Everyone in the bar went wild. He sang three songs and it was as wonderful as you would imagine.

After he played, his guy led Stevie back to their table. The faces in the window had multiplied, but the bartenders had locked the doors, so the window was as close as they were going to get.

The band finished their set and we worked our way through a couple more pitchers of that good legal beer. At the set break, Mr. Wonder apparently had to make use of the restroom located in the back of the bar, directly behind us. I watched in amazement as he and his guy made their way down the aisle toward us. The power that celebrities and heroes wield is strange. As Stevie Wonder walked past me, without thinking, I reached out and touched him - which cracked Lea and Brad up, I think, forever. It was just a little poke in the side, hopefully he didn't feel it. We got another pitcher and drank to our great good luck, and hoped in that youthful way that it might be an omen of good things to come.

A Fat Tire Story

Have you heard my Fat Tire story? It starts with my girlfriend Sara and I, who were living in Ft. Collins in an old house on a busy street. It was spring, and we decided to have a party.

We kicked around various ideas about who to invite and what kind of trouble to get into. One day, our friend Mark was hanging out. This was an old buddy of Sara's from high school. He had been working for a guy that was making beer in his basement. Mark said, "Do you want us to supply the beer?" We said sure. A plan was hatched whereby I would pick up a keg on Friday afternoon, the day of the party.

Friday rolled around and I drove into the Ft. Collins suburbs where the guy lived on a cul-de-sac at the end of a road. They told me to come around back to the basement to pick up the beer. I could smell the hops cooking from the street.

I went to the back, knocked on the door and Mark opened up. His work clothes consisted of white smock, tee-shirt, shorts, and Colorado sandals. He introduced me to his boss and they showed me around. It was an average sized basement crammed to the ceiling with two big tanks, myriad tubes, and a sink that ran the length of the wall. Mark grabbed a half keg container, washed it out and handed it to his boss, who filled it from the big tank. Bossman handed me the keg and said, "This is the first keg of Fat Tire beer." I paid him and thanked them and headed back to the house to get ready for the party.

I dug a pit in the back yard and put some bags of ice around the keg. We had some beers in the fridge to hold us until later. We wanted to save the good stuff for the party.

The party got rolling and we cracked open the keg. People started throwing down red plastic cupfuls of the stuff like it was Budweiser. Turns out, Fat Tire is far more potent than any cheap, mass produced American beer. While we were used to pounding brews all night, it became apparent right quick that that wasn't going to happen with this beer. There was a learning curve though, and this party was a first lesson for many in the joys and perils of the microbrew.

The party was a success. A fire was built and a fire truck appeared. There was an argument with the neighbor about bikes locked to the fence. Later, we crashed out under the stars to sleep off the magic while the dog circulated among us, sniffing to make sure we were still alive. We didn't even finish the keg. Mark came over at some point and had a cup or two.

Fat Tire became one of the most popular microbrews in America. I was in Bowling Green, Kentucky one night and spotted a Fat Tire tee-shirt on a gentleman whom I immediately regaled with my Fat Tire story. When someone says "Fat Tire is my favorite beer" - and it happens on a regular basis - they get the Fat Tire story. I pass a Fat Tire delivery truck in southern California on my way to work Tuesdays and Fridays, and have to refrain from stopping and telling the deliveryman my Fat Tire story. As the years go by, Fat Tire has taken it's rightful place in the pantheon of great American beers. Like all true fans, Sara, Mark, and I are proud that we were there in the beginning.

And that's my Fat Tire story.

Las Vegas

I went to something like thirty five Grateful Dead shows. By the time I moved to Colorado, I'd stopped traveling out of state and had to content myself with catching them annually at Red Rocks. One year, Sara and I got a wild hair and said fug that and drove to Las Vegas to catch a show.

It was late summer in the early nineties, I can't remember with certainty which year. Steve Miller was the opening act. I know it was summer because I remember the whole stadium being ringed with showers that they sprayed on the crowd. The only thing was, it was so hot that by the time the water hit you, it was pretty warm too.

We got there in the late afternoon. The show was scheduled to start just after the sun went down. The stadium was about ten miles outside of Vegas in the middle of the desert.We stayed in the car with the AC blasting until it was time to go see the show.

It's not difficult to find LSD at a Grateful Dead concert. By and by, a brightly dressed jester knocked on the window and offered us some. I hadn't tripped in years, and hadn't exactly planned to do so on this occasion, but acid is all about serendipity and we decided instantly that it was a fine day to Walk With The King. We bought a couple hits and tossed them down and laid our heads back and watched the sun turn orange over the Nevada desert.

You often don't notice that you're tripping until all of a sudden you notice you're tripping. We got out of the car and started walking. My strides were loooooonng and everything had that intense eternal quality, that sense that each moment is underlined somehow.

Inside, the Steve Miller Band was doing their thing. It was odd to hear the short, poppy tunes that were the bread and butter of so many radio playlists, elevator rides, and mall excursions in the real world. We wandered around with no particular purpose in mind, just seeking to take in the freaky vibes of a Dead crowd.

We found ourselves high in the stands. It was as if the drugs had led us there. The band kicked into Fly Like An Eagle as the acid trip intensified. We found a section of oddballs and sort of plopped ourselves in the middle of a crazy scene.

Dead fans are unusual people, but it was as if they had reserved a section for the craziest of the crazies. There was a guy in front of us with tattoos on every square inch of his body, and piercings everywhere else. To the left was a large, dark, dreadlocked lady. With supersonic LSD hearing, I overheard someone ask her, "Yo, dear, you still in nails?", to which she responded by raising a hand that had five of the longest, gnarliest fingernails I had ever seen. Twisting, knotted golden-brown branches that extended two or three feet from the end of her fingers. I looked at her other hand and it was the same. What the fuck? How did she button her shirts? Meanwhile, the Steve Miller Band kept flying like an eagle to the sea.

The good old Grateful Dead came out after dark. Jerry seemed to be in good spirits and wore a red tee-shirt for a change. We had one of those graceful trips where some otherworldly logic carries you from person to person, song to song, in a beautiful narrative all your own. We walked around the stadium, met people, danced, and got sprayed by warm, wet water. The band was on that night, and by the time they played the closing ballad we had been filled to the brim with all the goodness and love that you seek at a Grateful Dead concert..

We lingered for a bit. The acid made it all seem like it had gone by in a moment. The desert had cooled off and there were a billion stars in the sky. We must have hit each drum circle as we made our way out of the stadium into the parking lot. We kind of let people go by. We weren't in any hurry, still in thrall to the unspoken logic of the trip. We walked along like the dazed and happy hippies in the Woodstock movie.

The parking lot began to clear. We wandered here and there. Our thinkers still hadn't come back on. We just knew we would come upon the car at some point. Except we didn't. Our blissful wanderings took on a tinge of concern as the lots began to empty. We'd walked around the whole stadium and hadn't seen the car. Still, we were floating in the bubble of good tidings, and we knew we would get there.

All of a sudden, the lots were empty. We still hadn't seen the car. The only people left were the policemen and us. I asked one what we should do if we didn't find the car. He said, "Walk". We were already covered with sand, and Vegas was ten miles away. I began to start to begin to be slightly alarmed.

As we went around the stadium for what seemed like the tenth time, a car made it's way toward us. They stopped and asked if we had seen a german shepherd. We said no, but if they would let us ride along, we'd help them look for their dog while we looked for our car.

We all yelled "Champ" or "Russ" or something like that, I can't remember. It was the lost looking for the lost under the Vegas moon. All of a sudden, a lone car appeared. There it was. We must have walked by it ten times. We wished them luck finding their pooch and jumped out and got in our car.

The trip back to Vegas was glorious. We had just seen one of the best Dead shows ever, avoided catastrophe, and now we were headed home. We got to the hotel, parked the car, and re-immersed ourselves in the lights and sounds of the Strip. There were Deadheads everywhere.

Sara and I went to the room, washed the sand off our faces, and fell into each others arms, still high as hell. After a while, we put our clothes back on and went to the restaurant for midnight steak dinners, our trips slowly and peacefully winding down. A couple days later we would be back at work and school, but this had been a trip for the ages.

New Orleans

We drove through the night from the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and as the sun rose, we were in the swamps just outside New Orleans. Robin took the wheel and I tried to keep my eyes open as we headed for a hotel in the French Quarter where we would be staying.

We arrived at the hotel. A courtly gentleman took our bags and we got the key to the room. It had a balcony from which one could watch the bar fights at night - though we didn't know that yet. It also had a high, high ceiling and a four poster bed with a canopy. Everything was old and creaky and required a little extra push, but it was a legit proper old New Orleans room.

I tried to sleep but no luck, so we went out on the streets and looked around. One thing you may notice as you travel this big world - people's eyes say different things in different places. In the American Midwest, the eyes say, "Are you good?". In Santa Barbara, the eyes say "How rich are you?" In New Orleans, the eyes are quite different. As you walk the streets and glance around, the eyes in New Orleans ask, "Are you in on it?." It's as if everyone was at a secret voodoo ritual in the woods the night before and they want to know if you were there too. Did you see it?

We walked down the streets and looked in the stores. Many of them had voodoo shrines in the corner with signs that said, "Do not touch. No pictures." You might think these shrines are merely kitsch for the tourists until you catch the eye of the voodoo woman, rocking in her rocking chair. I boogied right quick out of a couple of them shops.

We walked over to an old bar and ordered Hurricanes. Hurricanes are large, potent rum drinks that you can get anywhere in New Orleans. We started drinking and got really sleepy. Robin knew all about ghosts. The Outer Banks are lousy with 'em, and she is able to see and feel if one is present. She said, "There're spirits all through here." I'm mostly of a mind to ignore them if they would be so kind as to return the favor, but the flesh crawled when she said that. I'd had my first encounter with a ghost not long before and the word, "uncanny" was invented to describe what it feels like to be in the presence of a ghost.

This brings up a question I've harbored, one which I'm sure no one besides those old voodoo women in the shops can answer: "What happened to all the ghosts in New Orleans after Katrina?" Did they migrate to other parts of town and take up new digs like so many of the people? Did they stay put, unaffected by the physical goings on of the world? I've asked people, and they look at me sideways. Not everyone has had a spirit guide like Robin.

One reason I wanted to go to New Orleans was to see some literary landmarks. We sauntered (we werestarting to get the Nawlins groove) over to, I believe it was Schawarps? Sharps?...some local drugstore outside of which the statue of Ignatius Jacques Reilly, protagonist of A Confederacy of Dunces, stood. He stood, frozen in bronze for eternity outside the drugstore with his lute string, waiting for his mother. They even got the flaps on his hat right; one down, and one straight out as he turned to listen down the street. We took pictures and such. My life is better knowing there's an Ignatius statue outside a drugstore in New Orleans.

The days passed. We did touristy things like eat beignets, walk through parks, and check out cathedrals. There were musicians everywhere. On any corner you'd see a small combo of old jazz cats making the most joyful sound. Have you ever noticed that oftentimes the best musicians have the most beat up, abused and broken down instruments? I saw this everywhere. A dude with an old beat up tuba, making our guts rumble. A rusty trombone, too old to reflect the sun, holding down the bass. They took pieces of junk and created heavenly music. Robindragged me away when it was time to go.

There was another literary trek I wanted to make. It was across the Mississippi in Algiers, so we took the mid-day ferry. As we disembarked, we saw the Mardi Gras floats docked there. It was odd to see such huge, ebullient creations out of season, inert and stored. We lingered a bit, and went looking for a po-boy.

The mission was to find the house that William S. Burroughs had lived in that had been depicted in Jack Kerouac's On The Road. In the book, Old Bull Lee (the Burroughs character) is a run down junky caught in a perpetual war with the Italian kids next door. He and the Kerouac character drink and throw knives at a board in their front yard. We had an address and got directions from a local and set off.

We had no idea how far away it was. We walked and walked through street after street of little identical houses. A van pulled up and the man waved us over. He said, "What are you guys up to?" We told him and he said, "You better not be in this neighborhood after sundown." I asked Robin if she wanted to go back, but she was brave, and this was a mission.

We picked it up and finally, finally came upon the house of Old Bull Lee. It was just like all the others. I could see why a writer would seek such a humble and presumably cheap place to call home. We took pictures and hopefully left the soul of the place intact.

It was getting dark as we hustled back for the ferry. We caught looks from some of the citizens but made it out of Algiers intact. The ride back was uneventful until a young guy approached us shortly after we disembarked. He had some weird rap about guessing where I bought my shoes, and dropped some calamine lotion on them to make me bend over so he could get at my wallet. I figured it out in time and straightened up and said, "Hey..." and he said "Welcome to New Orleans" as he dashed off.

The last day arrived and we packed up and got ready to leave. Robin went off with the doorman to sign out, and I went out on the balcony to check out the sights one last time. Ah, New Orleans. I stood there and took it all in. And took it in some more. Damn, they were taking a long time. I looked this way up the street, and that way down the street. I smiled and waved at the southern belles. Finally, I figured I'd go find out what was keeping them and headed back into the room and heard loud banging on the door. I opened it to a red-faced Robin and an impassive doorman. "Where have you been? We've been banging on this door for fifteen minutes. I left my keys inside." Ah, well. Life with the hearing impaired ain't pretty, baby. The gentleman grabbed our bags and we left that town.

Paris

We woke early on a rainy morning in Paris. It was summer, and we were on our honeymoon. The plan that day was to take a northbound train to Chartres Cathedral. I'd been there previously, and had been telling Megan all about the beautiful countryside, the little towns, and the tulip fields we would pass through - not to mention the glory of the cathedral itself. To see Chartres is to want to go back and see Chartres again.

I started the coffee and had a roll while Meg stayed in bed and tried to get a little more sleep. I was used to getting up early and exploring the neighborhood first thing in the morning. Our little room was in an old hotel by the Luxembourg Gardens, just a few blocks from Rue St. Michel. Each morning I'd walk down Michel to the lion at the foot of the street and watch the Seine as I had my morning coffee. Paris awoke late, and I liked to see the streets before the crowds arrived.

Meg sat up. I said, "Bonjour," and she just kind nodded and held her head funny. I sat on the bed next to her and said "hey baby," and gave her a kiss. She looked troubled, but I knew her well enough to wait, and she would tell me what was up when she was ready.

I got her some coffee and kept getting ready for our trip. As I came out of the bathroom she said, "Jack, I can't get this tissue out of my ear." She'd been putting pieces of tissue in her ears at night to block out my snoring. I took a look in her ear and couldn't see it. I checked my luggage for tweezers or a pin, but knew I didn't have anything like that.

I went to the front desk. The dudes down there were your typical haughty Frenchmen and didn't want to be bothered. I tried to convey our situation and we finally came to an understanding. He let me know that a doctor would come to our room.

I went back up and we waited for a half hour or so. Meg was stoic. I already knew she was tough. On the night she met my mother, Meg chipped a tooth during dinner and didn't say a word. I was still hoping we could get this taken care of and make the train for Chartres.

There was a knock at the door. The desk clerk and the doctor had arrived. I greeted them and let them in the room. The doctor went over to Megan, looked in her ear, and decided she had an infection. He began to write a prescription while we frantically tried to get across that there was something down in her ear. I tried to look sideways into his bag to see if there were some tweezers or something I could snag while he wasn't looking. He spoke no English, and each of our attempts to communicate seemed to be a further affront to his dignity. He did let us know that his visit would cost 50 francs.

There was no getting across to the doctor what was happening, so I paid him off and they left. It looked like we would miss our train. Meg was disappointed, and would have gone with the tissue in her ear, but I wasn't having it. I'd had a lifetime of ear trouble, and my sense was that you take care of ears immediately. And anyway, we'd been told that health care was free in Europe. All we'd have to do was find a clinic.

We put our coats on and headed back down to the desk. A different guy was on duty, but he was about as helpful as the first. I kept saying "clinic," thinking there must be one of those European free clinics somewhere in the area. He finally pointed down the street and I asked how far, and he said three or four, which I took to mean blocks.

We made our way out through the faded yellow foyer of the historic hotel into the street. It was gray and drizzly, and we dashed from awning to awning to stay dry. We passed the market that Meg liked to watch from the window, and the wall where the winos hung out, and found ourselves in an area we hadn't seen before. We came upon an impressive edifice, and Meg recognized the name of the building as the one the clerk had given us.

Inside we went, and down the corridor we walked. I popped my head in a few offices and said, "clinic?", and was met with more Parisian insouciance. We walked down halls and around corners, and finally realized we were at a university. At last we found someone that understood a little English, and she was able to point the way to what we were looking for.

Back down the street we went. This time it really was a clinic. Meg got an English speaking doctor and he got a pair of tweezers or a fish hook or something, and pulled that tissue clean out of her ear. The whole visit took about fifteen minutes, and no, it wasn't free.

There's no better feeling than having a physical blockage removed. Meg was liberated and it wasn't yet noon. The rain had stopped and we walked hand in hand through the Luxembourg Gardens back to the hotel. After exchanging snorts of derision with the clerk at the desk, we went up to our room. Meg took her spot on the ledge at the window, and I stretched out on the bed and took a look at the English newspaper. I don't remember what we did with the rest of our day, but I do remember that before we did it, we made love.

Father Browne

Raymond Frederick Browne. My father. Whose name I share with his other son.

My first memory of Ray - "Father Browne" in our family - was traveling to meet his family one Thanksgiving. He picked Kelly, Stacy, and I up in a Cadillac that smelled like a cigar. I remember being excited. I was a young boy and here was something different.

We drove to somewhere in Ohio. Cleveland? Hard to say. We met his family, but no one stood out except for his glamorous wife. What I remember most was going out back and playing football. It was a little pick-up game, maybe three on a side. Stacy might have played too. I tried to show off, hoping he would think I was good. Sports was my thing, and I was used to the approval of others because I was pretty good at the games I played.

We went home and grew up. Mom remarried a fine chap named Dick Mattingly who had three kids. We were a regular Brady Bunch. It was a lively family and there was a lot of laughter and good times. I was a jock, and played whatever sport was in season. I was pretty good, and quarterbacked the high school football team my senior year. I hesitate to mention that we did not win a game, but there you are.

I became a hippy and headed for the mountains of Colorado for college. It was a blast. I discovered philosophy, music, and a couple of fine women. I began to wonder about Ray during this time. I knew he was back in D.C., and that he had helped Stacy when she'd been in trouble, but I hadn't heard from him since that day we'd played football.

More from a sense of daring than anything else, I looked up his number and cold-called Ray from Kelly's bedroom when I was visiting one year during college. I got Ray's wife, who said, "Who is this?" to which I responded, "this is Ray's son Jack." She chuckled and said "wait a minute, I'll get him."

Ray came on the line. We talked for a minute and I asked if he would like to get together with Kelly and I. He didn't really hesitate, said yes, and suggested a restaurant. I didn't remember the area well, so I called Kelly to the phone. She said, "Who is it?" and I said, "Father Browne".

She was visibly nervous as she took the phone. He gave her directions to the restaurant and we agreed on a night to meet. Kelly hung up and turned to me and said, "Why in the hell did you do that?" more surprised than anything. I reveled in surprising people, doing the outrageous thing. That was what it meant to me until I met him.

We got there first, and when Ray approached the table, we stood up. He was in his D.C. correct business outfit - overcoat, jacket, tie - and removed one glove before he shook my hand. I can't remember whether he hugged Kelly.

We had an enjoyable meal. He told us that he'd been in a terrible motorcycle accident that hospitalized him for a year. He gave up drinking and met his future wife, and they moved to D.C. where he became what he'd always wanted to be - a politician. Ray become the shadow senator for the district and ended up getting re-elected two or three times.

We found out that he was back in D.C. through articles in the Washington Post that introduced the candidates and their backgrounds. They said that he was married and had three kids. He actually had six, and the discrepancy made my mom see red.

We asked if he would like to see us again. He didn't say no, but that was his answer. I went back to school and Kelly got married and started having babies. Ray lived just a few miles from Kelly, and this hurt her terribly. She'd been pretty quiet during our meal. She remembered him, and I don't think she knew what to do.

The years went by. Kelly and I started talking about Ray, and she let me know that she had been tremendously hurt by the whole thing. Many, many nights she cried herself to sleep in Matt's arms, asking the question that would come to haunt me, "Why doesn't he want to know me?"

One summer, she, Matt, and the kids were at a street fair in D.C. and they spotted Ray across the way. Matt was just plain mad about the whole thing. He grabbed one of their kids and took her over to Ray and said, "Ray Browne! This is your granddaughter." Ray made no move to hold her, or to acknowledge them.

More years went by. I looked up Ray and his family on the internet. I found out that he had another son named Raymond. It was as if I didn't exist.

Somehow, we found out he was dying of cancer. I think it took most of a spring to kill him. At some point, his sister asked him if he thought he should tell Kelly and I, and he said "no." The aunt later told Kelly that Ray was a secretive man, and kept much of his life to himself.

Raymond Frederick Browne had been a track star and a quarterback. He was a politician, sold insurance, and raised three children with his wife of over thirty years. They lived in a nice area of D.C, and on the day he died, the government lowered the flags in the district to half-mast. Many came to his funeral, and the words of praise were abundant and sincere. His son Ray II thanked him for always being there for him, and said how proud he was to be the son of such a good and loving man. I'm sure he meant it.

Doppelgänger

My doppelgänger is a middle aged black man. He appears fit. I can't tell if he is a street person or just a spirit traveling light. His clothes are plain, but not shabby. I first noticed him at the laundromat where he seemed to have some sort of job.

He would be there each time I went. I think I saw him sweeping, or taking out the trash, but mostly he would remove debris from the tops of the machines. We never made eye contact that I can recall, or if we did, there was no particular charge.

I couldn't figure out what he was doing there. Sometimes street people do a little work at a restaurant in exchange for food. I couldn't imagine what the laundromat gave him. Maybe free laundry services, but I never saw him with clothes, or actually doing laundry. In fact, I don't think I ever saw him talking to the people that worked there. He was just there.

I wouldn't have noticed him except that he was there every single time. We began to acknowledge each other. I don't know how, exactly. It wasn't a nod, or a look, certainly not a hello. But I could tell that he was aware of me, as I was aware of him.

I started seeing him walking down the street. No matter what time of day, more often than not, I would see him walking down the side of the road as I drove by. He never carried a bag, or pushed a cart. He always walked with purpose. So many guys on the street are just hanging around, but not this dude.

One morning I was sitting by the window at McDonald's having a McMuffin before work. I was absorbed in the newspaper so I didn't see him coming. All of a sudden, he walked by and knocked once on the window where I was sitting. He didn't stop walking, or look back. I looked up and thought, goddamn, it's him.

My marriage went south and I went north to Portland. I keep expecting to see him out of the corner of my eye, that same unobtrusive presence, walking down the street. Maybe we switched places. Maybe he is a happily married man living in the lap of luxury in Santa Barbara, and I am the quiet, dignified man of the streets, wandering the world.

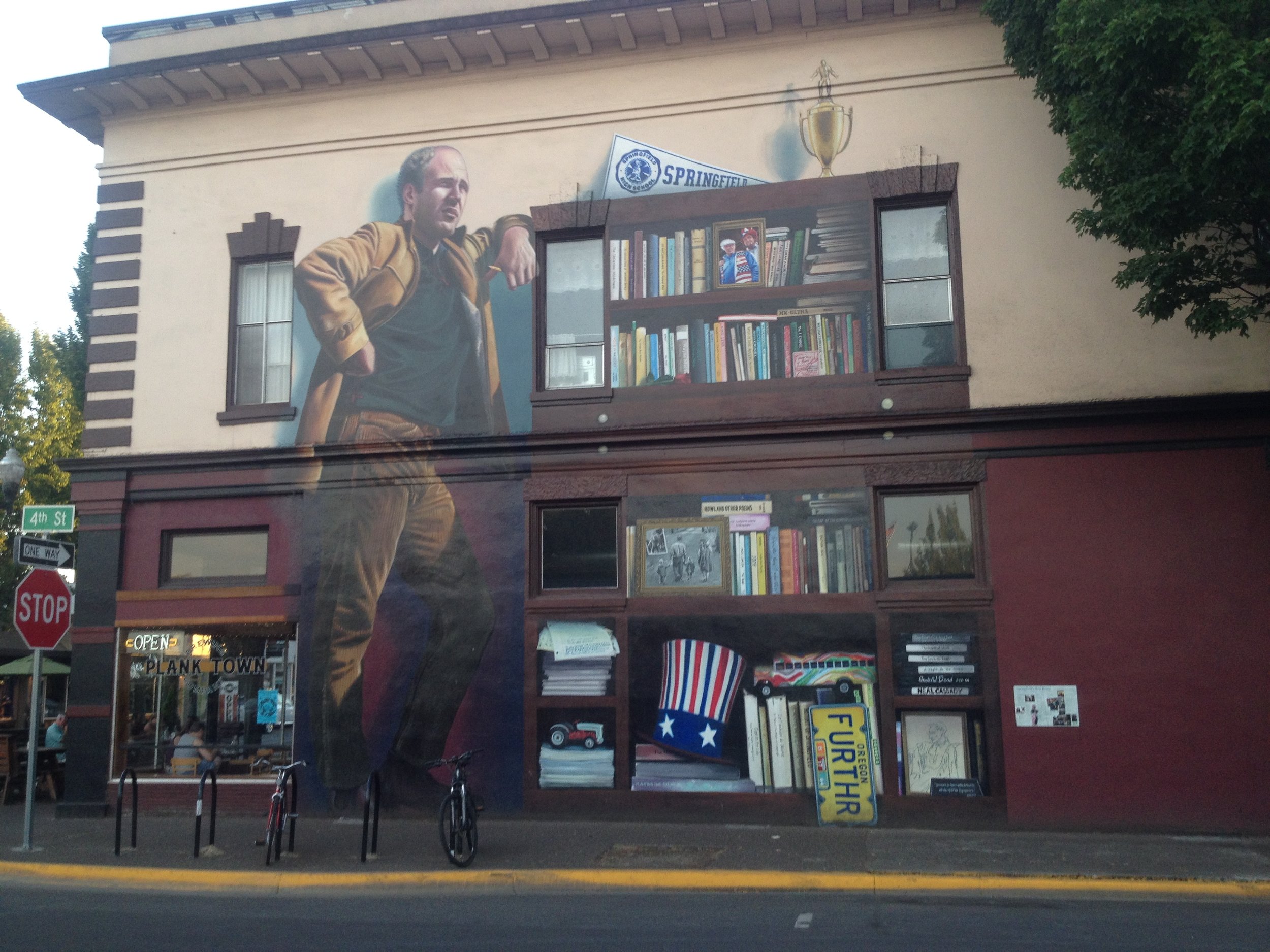

Eugene Is

1. Murals instead of graffitti

2. Go Ducks!

3. People hug like they mean it

4. Vendor at the Saturday market smokes a bong hit before conducting business

5. The drum circle at the Saturday market has been playing for 30 years

6. Each morning, street folk meet at the Ken Kesey statue in Ken Kesey Square

7. Portland and Boulder encourage themselves to "stay weird." Eugene has no choice in the matter

8. Surrounded by deep American farmland

9. You know how Steven Tyler of Aerosmith drapes his microphone with scarves? Eugeniuses do the same thing to their bikes - with flowers

10. A river runs through it

Why I am A Mysterian

In the world of academic philosophy, the term mysterian is primarily associated with a fellow named Colin McGinn. It refers to his refusal to take a position on what is called the "hard" problem of consciousness.

The hard problem of consciousness is this: How do you explain private, ephemeral, subjective ideas, memories, thoughts, etc. - consciousness - arising from physical neurological activity - the brain? Neural mapping has made progress toward such an understanding, but McGinn and his ilk claim that human beings have limited understanding, and some things, like the hard problem of consciousness, are beyond our comprehension.

I'm not using the term mysterian in this way. For me, it refers to not understanding the nature of God.

We are usually given three choices, or positions, regarding the nature of God. These are: believer, atheist, and agnostic. The believer "believes in" the existence of God. The atheist "believes" that God does not exist. The agnostic withholds belief, but is willing to keep her mind open to new evidence. A mysterian finds that he knows nothing about the nature of God, yet has a need for activity such as prayer and worship that is traditionally considered "religious."

I borrowed the term mysterian from McGinn after reading Stephen Mitchell's translation of the Book of Job. I think it's an apt depiction of Job's view of God at the end of the story.

In the story, the Devil bets God that he can make Job curse God's name. God says, "go for it." The devil takes everything from Job and leaves him scraping his sores by the side of the road.

Job's suffering is witnessed by his friends. After a period of sitting silently with Job, his friends tell him that he is getting what he deserves. Surely Job must have committed some ghastly sin for God to make him suffer so. But Job hasn't, and he tells them this. They can't believe him because they believe in the Santa Claus theory of God.

The Santa Claus theory of God (my phrase) says that God is like Santa Claus, rewarding the good and punishing the bad. He sees you when you're sleeping and knows when you're awake, and your good or bad fortune is a direct outcome of your virtues and sins. People have always believed this, though it is obviously not true.

Bad things happen to good people. Good things happen to bad people. We all know this. It's one of life's cunundrums. Why does an innocent child get cancer and die? Why do natural disasters wipe out whole towns? Why? Jobs friends - and someone like Pat Robertson - would say that the victims must have done something wrong, or if you believe in karma, may have done something wrong in a former life.

For some reason, we want to believe that life makes sense, that there is a reason why things happen, a benevolent Santa dispensing justice in the sky. That's why Job's friends insist that he must have done something wrong. But Job insists that he hasn't, and keeps insisting. Driven crazy by his accusatory friends, Job screams from the center of his being, "I did nothing wrong. Fuck this and fuck you, God."

God hears. After remonstrating with Job a bit - where were you when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy? - he says that among his friends, Job was the only one who told the truth. Everything was restored to Job, and he lived to an old age and died peacefully with his family around him.

God is saying that we don't know. We aren't supposed to know why things happen. Tell the truth. Suffer. Don't make up idiotic stories to avoid the suffering of others. Behold, it is very good.

A mysterian doesn't "believe" in God. A mysterian accepts that the nature of God is a mystery. But this need not stop one from worshiping the source of creation. One prays without needing to understand that to which one is praying. One need not pledge allegiance to some corny concept of God/Santa (believer), reject wonder altogether (atheist), or wait for evidence supporting such foolishness (agnostic). A mysterian knows that he does not know.

And that's why I'm a mysterian.

Hurricane

Five A.M. and the wind has shifted. Bill nails plywood over the windows while Jen drives to the store for enough supplies to last through a hurricane. Most of the neighbors have left the island, heeding official warnings.

The house begins to shake on it's stilts. Bill hears a trashcan rolling down the street and smiles at his wife.

"Been awhile."

"Five years," says Jen, as she brings Bill a beer. They make a party of it during a hurricane since there is exactly nothing else to do. No T.V., internet or phone, and the power usually gives out at some point.

"Did you get the candles out babe?"

Jen points to the kitchen counter where there is a pile of black, blue, and turquoise candles and a box of long kitchen matches, unused since the last hurricane.

Jen is a fifth grade teacher. Bill is semi-retired. He spends his time repairing things and drinking coffee with his friends at McDonald's. He misses working on the island ferry - a job he held for thirty four years - but knows other, younger men need to support their families, so when they offered early retirement, he took it. They have three kids that did what most kids on the island do - leave. But they didn't go far, and come back when they can.

"Do you remember the year the eye passed over the point and blew out the windows and soaked the carpet?"

"How could I forget? It was the only way I could get you to replace those ugly orange carpets."

Bill finishes his beer and goes to the fridge for another.

"Want one?"

Jen nods. The light is brightening around the edges of the plywood, though they know they won't see the sun for a few days. The house begins to shake harder.

"You ever see Betty Smith at school these days?"

"She substitutes, and comes in for staff parties once in a while. Why do you ask?"

"John says she hasn't been feeling well. They don't know what's wrong and she won't go to the doctor."

Something thumps against the house. "I better go check that," says Bill, and puts on his coat and hat. He opens the front door carefully. The wind is blowing about forty knots, not enough to knock a man over, but stiff enough to make him grab a rail, which Bill does as he goes down the steps to the yard.

Water from the bay is coming over the bulkhead. If the wind picks up - when the wind picks up - they'll have a small lake under the house. It's a good thing they moved the cars to higher ground yesterday.

Bill sees an oar from his jimmy boat in the yard, which must have been what slammed into the house. The door to the shed almost rips off in his hand as he puts the oar inside. Bill notices a light on at the Smith's house across the street.

Back inside, Bill says, "Looks like John and Betty stayed."

"Really? They never stay. Are the lights on?"

"Yep."

Jen lights a candle and grabs a pack of playing cards. They play a couple hands of rummy while the storm picks up steadily outside.

"Do you remember that time Don got on his Big Wheel and rode all the way to the drug store to buy candy? What was he, three years old?" Don is their eldest. He owns a construction company on the mainland.

"Yes I do. Scared the life out of me. I'll never forget that pharmacist calling and saying, 'You'll never believe who just walked in the door.'"

They laugh, and look in each others eyes. Jen is one of those women that will be beautiful every day of her life. Her once long, wavy brown hair is now cut just below her ears, and has as much gray as brown in it. Her eyes are clear. The lines on her face only seem to emphasize her delicate features.

"We've had a pretty good run, haven't we baby?"

"Yes we have, Dollar Bill."

Suddenly, there's a pounding at the door. Bill knows it isn't an oar or the wind this time. He goes to the door and looks out the peephole. John Smith is standing there, looking upset.

"John, come in, come in, surprised to see you all still here."

John comes in and walks to the center of the room, turns his face toward the ceiling, and starts to howl. After a stunned moment, Jen walks over and touches his shoulder.

"John?"

He looks at Jen and says, "Betty, she's. Betty........she's" He wrings his hands and asks Jen something with his eyes.

"She's dead."

Bill asks, "John, what happened?"

John looks at him with the eyes of one who has seen, but doesn't understand.

They guide him to the couch and pull their chairs up close. Jen puts her hand on John's knee and they wait.

"She's been sick. She was sick most of the time, but didn't want anyone to know. I begged her to go to the doctor, but she wouldn't, saying whatever it was would pass. She didn't seem to be in pain, exactly. She just had less and less energy. She laid down for a nap this morning. When I went up to check on her, she was gone.

John looks at his hands. He has been their neighbor for more than twenty years. He'd met Betty, who was a local, soon after he arrived. They dated for a while and got married inside of a year. It had been a big deal on our little island.

Jen asks if John would like some water. He nods and she goes into the kitchen. The wind is really howling now. The eye of the storm isn't far off. John and Bill look at each other. They are the types that stay during a storm, the types that fix what is broken, and rebuild what can't be fixed. Bill puts his hand on his friend's shoulder as the storm rages on.

273

Gray the color of sadness. The color of ocean, miles from shore.

The color of age. The Portland sky.

November 2015, the month I moved to Portland, was the rainiest on record. I had just gotten divorced and was unemployed. I spent a good deal of time either at the window watching the biblical deluge, or lying on my bed staring at the ceiling. I've always had a natural ability to meditate. As a boy, I would stare at my bedroom wallpaper with it's repetitive design and spontaneously meditate. I called it "going around the world in my head." I came out of it incredibly refreshed. My Mom would ask me, "Why are you so happy?"

I began spontaneously meditating again on those rainy days in Portland. I had lost everything and there was nothing to do but go inside. Here's what I found.

You can close your eyes and walk down the corridor of your mind. In the first room are today's thoughts: "What's for breakfast?,""I'm late," - things like that. Further down the hall you can open the door to the more persistent personal myths. Thoughts like, "I should have hit on that girl," "They will always leave me," abide here. Further still down the hall is the realm of the collective unconscious. One can meet Kings, Queens, Earth Mothers, and Wise Old Men there. That was as far as I had ever gotten in meditation.

One day I went so far into my mind that I passed through all those rooms and kept going down the hall - I had nothing to lose - and came to a door I'd never opened before. In this room was smells. I kid you not. I could remember what specific people and things from the past smelled like. I smelled the rosewater perfume of the old lady that lived across the street when I was a child. Then I consciously shifted to another spot where I smelled the breath of a friend after eating doritoes. I remembered six or seven distinct smells, several from early childhood. Then I began to freak out and came back to the room and the rain.

But I'm here to tell you that this place exists. A "room" in your mind where everything you've ever smelled is preserved and is accessible. It's there. I smelled it.

Sam's

Life - itself - on a random afternoon in a West Eugene bar. The buxom bartenders in their low slung blouses efficiently dispense drinks to the regulars around the bar. A large, red faced man declaims frantically as the lady next to him laughs into her hand. A golden late afternoon light, bright and fading, softens their faces.

A line forms at the register. This is a neighborhood bar and everyone knows each other. They hug like long lost loves though they have been seeing each other daily for years. A small, slim lady with flowing gray hair blanks on my knowing smile as she slips out the door with a guy to smoke a joint.

I'm at the front of the line and the bartender gives me a "my eyes are up here" smile. I order a scotch and beer. A bird swoops in through the front door and flies in mad circles over our heads. We watch and try to will it through the back door with our eyes. The bird bangs against the wall a few times before winging to freedom. We all cheer.

A young, slim, extremely attractive redhead comes over and stands next to me. We watch the comedy show that has begun onstage across the room. I check her out and laugh a little harder at the jokes than I might have otherwise. I'm guessing she's in her mid-twenties. She could be the daughter of the woman who has just left me. I let the moment pass and she drifts away.

The stoner and her guy come back in. A joint rolls out of her pocket on to the floor. I grab it and tap her on the shoulder. She thanks me and puts it back in her pocket. She still doesn't recognize me from the conversation we had a few weeks ago. She's a grandmother and has lived in Eugene her whole life.

I go outside to check out the Irish jam on the back patio. My friends John and his wife Sheila are at a table in the front. We hug and shake hands and they make room for me. John is a garrulous Greek ex-jock and Sheila plays piccolo with the group.

John says, "Got a job yet?"

I say, "Nope, still looking."

He smiles and says, "Keep looking brother. You still got a little shit in ya. Something will happen."

We rap it out and an hour passes along with my beer. I go back in the bar and the redhead has left. I extend an invisible leg out behind me and kick myself in the ass.

The bartender pours another scotch and beer and I take them to a table in the corner. Dusk has fallen. I came in today for a few quick drinks before yet another attempt to fly right and quit drinking. It's easy to see that that's not going to happen.

Springfield Is

1. The most complete rainbows I've ever seen. Purples, reds, greens, blues, yellows - the whole spectrum. Also, one can see just where they end.

2. "Springtucky" to the more fashionable denizens of Eugene.

3. Miles of abject poverty, one step up from a Brazilian favela. People work two or three jobs and still go into debt. Meth.

4. Country folk. Holding the door for others. "Have a nice day.""You're welcome."

5. They bring water and bag groceries without your having to ask.

6. An obvious drug dealer yells from the door of a bar, "Pay me fifty dollars on the first of every month.""Love you, man," replies the dude in the parking lot.""Love you too," replies the dealer.

Mutual Arising And Trump

"Apologize? If you truly want to apologize, you have to apologize for your whole life. No one can do that." - Jack Browne

It's one hundred years in the future. A group of people gather around a table in a neighborhood bar. Someone poses the question: What if Donald Trump had never been President?

A lively discussion ensues. Various outcomes are proposed. Jim claims that WW3 never would have happened. Albert says that without widespread deregulation, the great crash of 2034 would't have occurred. And so on.

They are are doing what is known as counterfactual history. This is a method that explores history by means of extrapolating a timeline in which certain key historical events didn't happen or had an outcome which was different from that which did in fact occur.

Scholars use counterfactual history to investigate questions like,"What if the railroads had never been invented?" or "What would have happened had Hitler died in the July 1944 assassination attempt?" Counterfactual history depends on the assumption that you can take one event out of history, and everything else will stay the same. This is not possible, and I'll tell you why.

Pratityasamutpada is a central tenant in Buddhism. It has been translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising. This is the idea that there is nothing independent except Nirvana. All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other pre-existing states, and in turn, from them arise other dependent states, while they cease. The main point is that everything causes everything. Nothing can be left out - except Nirvana.

What does this mean in a person's life? You can't look back and say, "Oh, if I had only stayed in school and gotten that degree, all would be well." You don't know that. Everything else would change too. If you had stayed in school you might have lost your life in an earthquake. You might have joined a cult. And so on.

Not only does changing one event for you change everything for you, it changes everything for everyone else too. Perhaps staying in school forced you to get a job at a coffeehouse where you spilled hot coffee on a customer. Said customer then sued the coffeehouse, retired to the country, and wrote epic poetry that changed the world forever. And so on.

As with everything else these days, it all comes back to Trump. Accepting mutual arising makes two things clear about the phenomenon of President Trump.

First, we are Trump. Trump is us. Everything causes everything. He would never have been elected without the passivity of the 50% of the electorate that did not vote. Further, Trump could only be elected in a celebrity worshiping culture where more young people know the names of the Kardashians than know the name of the Vice-President. He is us and we are him.

A second thing to see about Trump and mutual arising is that one must not be passive. There is a mood of great despair for many Americans right now. It is as if a Trump presidency dooms us in some way. Maybe it does - in some way. But everything causes everything. The future is unwritten.

258

Blackout

All of the sudden, he woke up with that feeling. There was a pain in his upper thigh where he'd been laying on a set of keys. He raised his head and looked around the room at the ghostly outlines of the familiar things. He could not remember what he'd done, or where he had been. It was as if a piece of his soul was missing.

He made his way down the steps, trying not to knock any of the pictures off the walls. Someone was up downstairs. The lights were burning. He hesitated on the landing, but his need for a glass of water carried him on.

They were all up. His wife, his mother-in-law, and his father-in-law. Even the dogs. They were arrayed about the brightly lit living room like characters in a painting. He walked through the scene to the kitchen. He opened the cabinet and grabbed the familiar glass. It looked like something an astronaut had brought back from the moon.

As he was filling his second glass and wondering what to do next, Allen realized he was wearing his underwear and a sweat soaked tee shirt. He drank like he always drank, aiming for the bottom of the glass. He'd heard them say a few words, but wasn't nearly awake enough to have any idea what they were. As he finished the water, his dog, Old Rufus, came into the kitchen and rubbed against his leg. Allen reached down and scratched him behind the ears.

A decision needed to be made. Allen stood in the dark kitchen, knowing he must act, waiting for the voice of God to tell him what to do, but the only thing he could hear was the muffled words from the other room. Old Rufus moved closer and let out a moan.

Allen knew he'd done something wrong, and knew that the wrong was located somewhere in a blackout. He remembered getting the keys from his father-in-law after dinner. No, on second thought, he realized he'd actually swiped them from the spare key rack and slipped out the door. But beyond that, the mists would not part, and remained stubbornly enshrouded around the lost evening.

Allen shot through the living room like a football player running to daylight. He looked at no one and mumbled, "I'll be right back." He went up the stairs and into the room thinking, "Don't turn on the lights. Do not turn on the lights." Then it would be real, which was the last thing he wanted.

He felt around for some sweatpants and a dry tee shirt. Every movement cost him something. He felt like he was in a realm of the soul where the scales of justice weighed against him with the simplicity of the score on a pinball machine.

That was it. They'd gone out to a pub and played pinball. He couldn't remember any more. He took his sweaty night clothes off like a bad memory - which they were - and put the clean stuff on. The shirt was on backwards. It was all he could do to take it off, turn it around, and put it back on. He sat down on the bed. No escape, no escape. If only he could remember what he'd done.

Onward was the law of his soul these days. He pushed off the bed and went back down the steps to his family. As he stood where the darkness met the lights of the living room, he looked at them closely.

Bill, his father-in-law, looked back at him. His mother-in-law, Emily, was busy doing something with her hands. He looked at Phoebe, his wife. Her cheeks were wet, and her legs were pulled up to her chest with her arms around them. She wore a soft green tee shirt that he knew was clean and would smell good. Allen looked down at his feet, and back up at his family and said, "Well."

He took his place on the couch next to Phoebe, but they did not touch. He knew that they would, eventually, and he was willing to go through any rite, any penance, pay any awful price to get from here to there. He resisted the urge to reach over and touch her foot.

Bill started talking in his even, rhythmic way. Allen watched the words go by like the stock report on the evening news. Bill said that he had found the car parked sideways, doors open, in the driveway a while ago. There were fast food wrappers on the floor and barbeque sauce smeared across the steering wheel and on to the windshield. It smelled like beer, and other things. What had he done this evening?

Allen took it in. He remembered nothing after the pinball machines. When should he look at them? He was beyond shame. He felt like his head had been cut off.

Allen looked up at Bill and Emily. They were getting older. Their eyes were at once bewildered and understanding. He loved them. Allen began to sob. At first in his body, and then his shoulders caught it, and then it came through his mouth and out of his eyes. They were around him with their arms and voices. He didn't want to remember now. He just wanted this. Phoebe held him until the sobs went through his body and away.

Allen gave Bill his keys back, then Bill and Emily went off to bed. The dogs were on the couch next to them. Allen still hadn't said anything. He could barely look at her. They sat like that for a while, and then Phoebe said, "Come with me."

She led the way to a closet where they stored things. She wanted to show Allen something, and dug through the boxes until she found what she was looking for. As she stood up, Allen could see that she was crying again.

In her hand was a piece of cloth. She gave him one side of it, and they carefully opened it. It was an old valentine they'd made each other in the early days of their love. They looked at it in wonder. Those days, those marvelous days, and here was the valentine. Allen tried to speak, but the words were stuck in his throat. Phoebe waited to hear what he would say.

257

Friendship Mountain

Out among the elderberries and taproot, the passion fruit and chapperelle, looms Friendship Mountain. Your guide, Ahmed, awaits you there. He will take you to the peak where you will meet your best friend, who will remain your best friend forever.

Ahmed greets you with a bow and a friendly smile. He's not young, but spry and athletic, for he has spent his life guiding pilgrims up the mountain. He beckons you into a hut where you are served elderberry tea. Ahmed does not speak, but communicates with expressions and gestures.

Once tea has been consumed, Ahmed grabs two faded brown backpacks from the corner. These are your provisions. Ahmed indicates that you are not to investigate the items in your pack. One is to trust Ahmed, and to follow instructions.

The way up Friendship Mountain is long. In fact, it's endless. One is scratched by the overgrown chapperelle that knots the path. One is always lost. One follows Ahmed, and sometimes even loses sight of him, but Ahmed awaits you with a smile around the bend, and you continue.

Fierce storms break with no warning any time of the day or night, but warm clothes and sustenance are to be found in your backpack. You hear wild beasts keening and roaring in the distance. You will meet each of these animals on your journey. Some you will eat, and some will eat you, according to the ancient law.

You look down on the busy people of the town as you climb Friendship Mountain. They are unaware of your journey. You recognize a face here or there, but as you rise, the life below becomes but a hum, and then is forgotten. Life on the mountain is different.

How different, you ask? Different as the day from the night, as the baby from the elder, which is to say, not different at all - but seen from the other side. You never know where you are, or where you're going, but you trust Ahmed to take you there. One only needs trust to climb Friendship Mountain.

When does one reach the peak and meet one's best friend? Remember, life is different here, and is to be seen from the other side. What is this peak, this destination, even the other that one seeks? The questions are only clues and pointers. One need only trust Ahmed, and all shall be revealed.